Differentiating Fluency Instruction: The Importance of Leveled Texts

Every classroom includes students with a wide range of reading abilities. Some students read fluently and effortlessly, while others struggle to decode, phrase, or sustain comprehension. Differentiating instruction to meet these varied needs can feel daunting. One effective solution is the use of leveled fluency passages. These allow each student to practice at an appropriate level while still working toward common goals of accuracy, automaticity, and comprehension.

Why Differentiation Matters in Fluency

Fluency is not a single skill—it is a blend of accuracy, rate, prosody, and comprehension. When students practice with texts that are too difficult, their cognitive energy is consumed by decoding. This leaves little capacity for expression or meaning-making. Conversely, when texts are too easy, students miss opportunities to stretch and refine their skills. Research shows that fluency development is most effective when students read materials that fall within their instructional level. It should provide challenge without overwhelming them 1.

The Role of Leveled Passages

Leveled passages make it possible for teachers to:

- Provide targeted support: Students who struggle with automaticity can work with shorter, decodable texts, while more fluent peers practice with complex syntax and advanced vocabulary.

- Promote growth across a continuum: As students progress, new passages are introduced to reflect higher-level demands.

- Encourage repeated reading: Leveled passages are ideal for practices such as timed repeated reading, which has been shown to significantly increase oral reading fluency 2.

- Support comprehension through prosody: Passages of varying difficulty help students practice reading with expression and phrasing, reinforcing meaning-making 3.

Differentiation in Action with Flow Reading Fluency

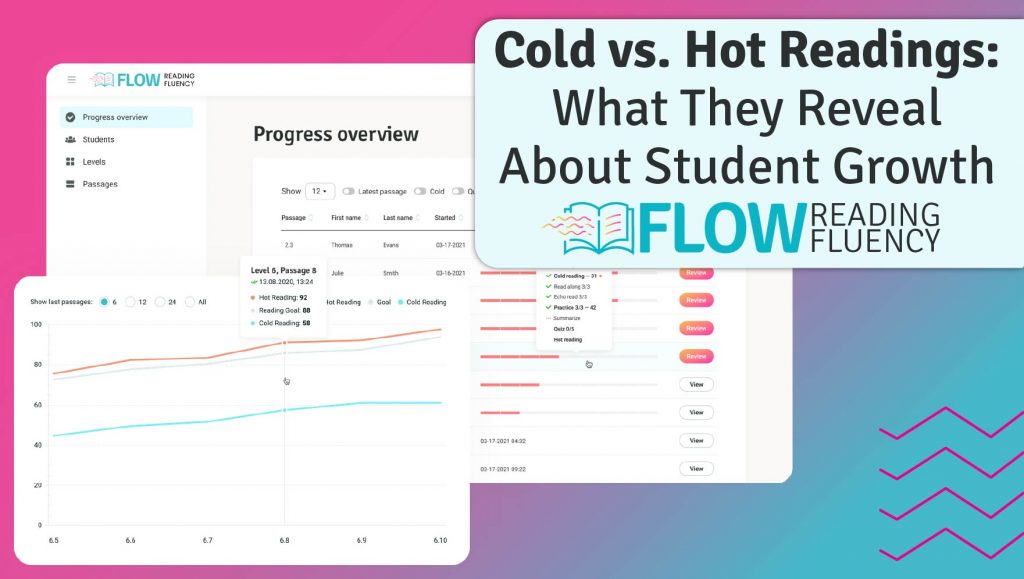

The Flow Reading Fluency program provides teachers and parents with over 240 leveled passages. These range across grade levels and text types. Within Flow, students complete both “cold” (unpracticed) and “hot” (practiced) readings of the same passage. This structure allows educators to monitor growth not just in rate, but also in accuracy and expression.

Because passages are leveled, teachers can assign texts that align with each student’s fluency profile. A fifth-grade classroom might have students reading anywhere from late second-grade passages to middle school-level texts. All students use the same platform. The data—displayed in clear charts and graphs—makes it easy to track progress, set goals, and communicate growth to students and families.

Practical Benefits of Leveled Fluency Practice

- Equity in instruction: Every student receives texts that are appropriately challenging.

- Efficiency for teachers: Ready-made leveled passages reduce the time needed to prepare differentiated materials.

- Motivation for students: Visible progress on leveled texts builds confidence and encourages persistence.

Final Thoughts

Differentiated fluency instruction ensures that no student is left behind or left unchallenged. By pairing research-based practices with leveled passages, teachers can create a structured yet flexible pathway for every reader. Flow Reading Fluency provides the tools to make this differentiation both manageable and effective. This helps all students build the automaticity, expression, and comprehension they need to thrive.

References

- Kuhn, M. R., Schwanenflugel, P. J., & Meisinger, E. B. (2010). Aligning theory and assessment of reading fluency: Automaticity, prosody, and definitions of fluency. Reading Research Quarterly, 45(2), 230–251. ↩︎

- Therrien, W. J. (2004). Fluency and comprehension gains as a result of repeated reading: A meta-analysis. Remedial and Special Education, 25(4), 252–261. ↩︎

- Miller, J., & Schwanenflugel, P. J. (2008). A longitudinal study of the development of reading prosody as a dimension of oral reading fluency in early elementary school children. Reading Research Quarterly, 43(4), 336–354. ↩︎