Understanding ORF (Oral Reading Fluency) Norms and Benchmarks

Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) is one of the most widely used and reliable indicators of a student’s reading development1. By measuring words correct per minute (WCPM), educators gain valuable insight into a child’s ability to decode, read with automaticity, and comprehend text. Understanding ORF norms and benchmarks is essential for setting instructional goals, identifying students who need intervention, and tracking growth over time.

What Are ORF Norms?

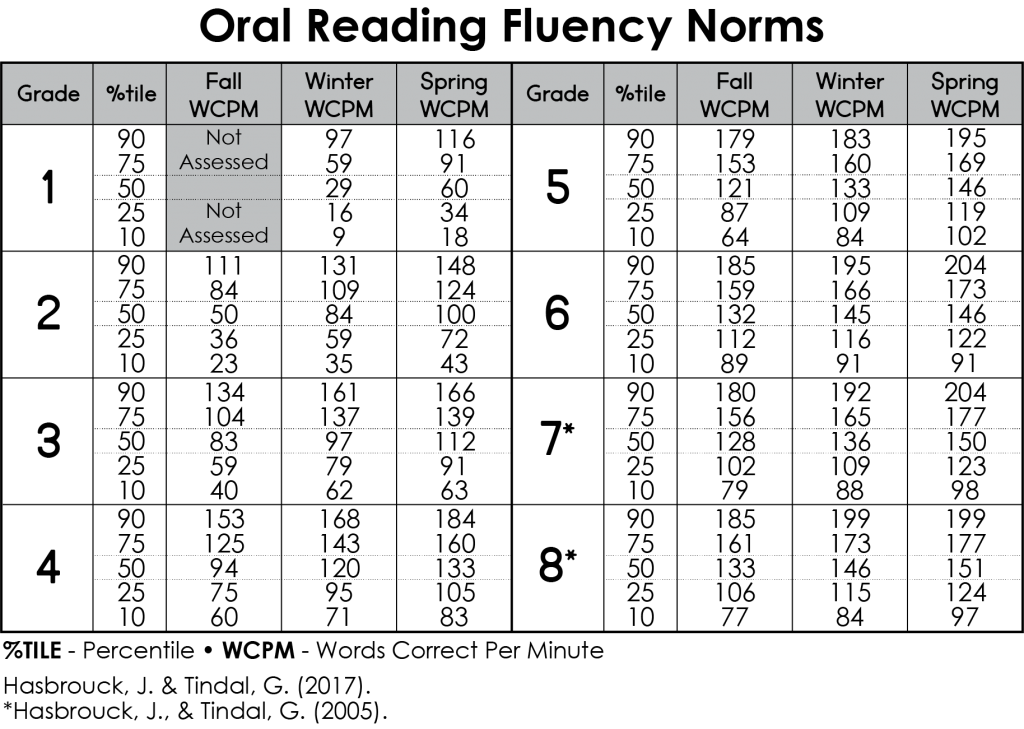

ORF norms are grade-level expectations based on large-scale research that captures the range of fluency rates for students across the United States. For example, national ORF norms developed by Hasbrouck and Tindal provide benchmarks from grades 1–8, showing expected WCPM growth from fall to spring. These norms give teachers a frame of reference to determine whether a student is meeting, exceeding, or falling below grade-level expectations.

In practice, a third-grade student at the 75th percentile might read 104 WCPM in the fall, while a peer at the 25th percentile may read fewer than 60 WCPM at the same time of year. This gap not only persists but often widens as students progress through grade levels without targeted fluency support.

Why ORF Benchmarks Matter

Benchmarks function as performance goals—targets that indicate whether a student is on track to achieve grade-level reading proficiency. For instance, if a fourth grader’s ORF score falls below benchmark levels, it is a strong signal that the student may also struggle with comprehension. Research consistently demonstrates that fluency and comprehension are closely linked. In fact, oral reading fluency has one of the strongest correlations to reading comprehension of any single measure2.

By using benchmarks, educators can:

- Screen students early in the year to identify those at risk.

- Monitor progress through midyear and end-of-year checks.

- Differentiate instruction by grouping students according to their fluency needs.

- Communicate with parents about growth relative to grade-level expectations.

Using ORF Data for Instruction

ORF assessments should never be used in isolation. Instead, they are most powerful when paired with diagnostic data and classroom observations. For example:

- A student with low WCPM but strong accuracy may need repeated reading practice to build automaticity.

- A student with high WCPM but poor expression (prosody) may benefit from phrase reading or choral reading strategies.

- A student consistently below benchmark may need explicit fluency intervention, such as audio- or video-assisted repeated reading.

The Role of Flow Reading Fluency

Tools like Flow Reading Fluency make ORF assessment and practice accessible for classrooms and homes. Students complete cold and hot readings of leveled passages, and their growth is tracked with clear charts and graphs. This allows teachers and parents to quickly see whether students are meeting ORF benchmarks and to provide meaningful support when they are not.

Final Thoughts

ORF norms and benchmarks provide more than just numbers on a chart—they are powerful tools for equity and early intervention. By understanding where students are in relation to national expectations, educators can close gaps before they widen, ensuring that all readers build the fluency skills needed for lifelong comprehension.

References

- Hasbrouck, J., & Tindal, G. (2017). An update to compiled ORF norms (Technical Report No. 1702). University of Oregon, Behavioral Research and Teaching. ↩︎

- Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M. K., & Jenkins, J. R. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(3), 239–256. ↩︎